Great Movies That Barely Resemble the Books They’re Based On

When deviating from the page makes for a unique adaptation, and when the book required a closer read.

What does it take for a movie adaptation to transcend its source material? Many a filmmaker uses a book as a blueprint (whether or not they read it in its entirety) but take creative license to put their own unique stylistic and/or thematic spin on what is necessarily a much more visual story than the original one on the page. Often that’s taking a key character—whether a comic book antihero or an unnamed book protagonist—and giving them an entirely new backstory or quest. Or choosing a different point of view that opens up new storytelling avenues. In some cases, book and movie follow the same premise but diverge wildly at the end… or they do reach the same narrative conclusion, but on radically different paths that will leave you with very different emotional reactions as a viewer.

Here are eight great movies based on books that may share titles or a few similarities with their source material but then go their own way…

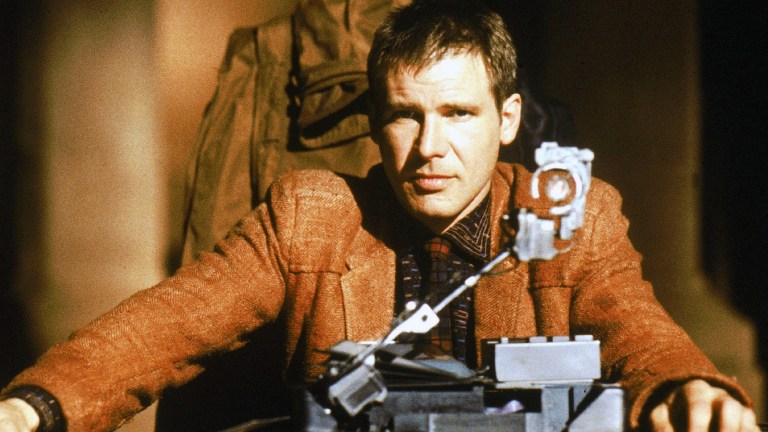

Blade Runner

All of your favorite details about Ridley Scott’s 1982 sci-fi classic have little to do with Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, the 1968 Philip K. Dick novel on which it’s based. For one, Scott nabbed the term “blade runner” from two sci-fi novels in the 1970s (one by William S. Burroughs, in turn based on another by Alan E. Nourse), despite them having nothing to do with Dick’s original plot about bounty hunter Rick Deckard killing rogue androids. Calling them “replicants” is another movie-specific detail, as the film really expounds on the question of whether these lifelike robots can possess the same or even greater emotions as humans.

Ironically, book Deckard is more of an unhappily married sad-sack who becomes dehumanized in hunting down androids, while Harrison Ford’s unforgettable performance starts out as a cynical bachelor who finds himself falling in love with replicant Rachael (Sean Young), who herself struggles with implanted memories that make her believe she is human. Blade Runner’s iconic neo-noir aesthetic excellently sets up the various replicants’ identity crises, with Roy Batty’s (Rutger Hauer) emotional “tears in the rain” speech demonstrating just how much these androids feel, and dream of, and give up at the end of their lifespans.

Constantine

If you put Keanu Reeves’ brooding, terminal-cancer-diagnosis exorcist beside the DC TV universe’s blonde, trenchcoat-wearing, bisexual comic book inspiration, they would look like night and day. But Keanu’s was the first John Constantine to make it from page to screen in the very loose 2005 adaptation of the Vertigo Comics series Hellblazer, a superhero movie that feels more like a standalone angels-versus-demons contemporary fantasy.

Francis Lawrence’s film is pretty drenched in Catholicism, with the eponymous character stuck in a sort of purgatory on Earth (with the ticking bomb of lung cancer, of course) due to committing suicide in his youth yet being revived to keep facing the demons he was trying to escape. His investigation into the mysterious death of a devout Catholic woman (Rachel Weisz, also playing her detective twin sister) who supposedly killed herself reveals the thinning barrier between Heaven and Hell, and puts Constantine into the path both of archangel Gabriel (Tilda Swinton) and vindictive Lucifer (Peter Stormare). There’s sacrifice and redemption and a resurrection of sorts, but the Constantine who comes out the other side ready for sequels—though one wasn’t even a possibility until 2022—is very different from the comics-accurate con man and occult expert (Matt Ryan) who made his way to the Arrowverse in the 2014 TV series Constantine, and especially not the genderswapped Johanna Constantine (Jenna Coleman) in the 2022 series The Sandman.

Children of Men

Alfonso Cuarón made a point of not reading P.D. James’ 1992 dystopian novel before embarking on his celebrated adaptation in 2006. This was due in part to the project already having a screenplay that had undergone rewrites, as well as Cuarón’s own worry that he would “second-guess” any creative decisions. While he kept the same premise—a near-future plagued by infertility, in which England has cut itself off from climate refugees—he referred to a summary of the novel instead of the entire text. The fact that he was developing the project immediately post-9/11 contributed to grounding this infertility dystopia more in the present, plus inviting star Clive Owen to contribute enough dialogue and interiority to his character Theo Faron that he earned a co-writing credit.

James’ novel contextualizes the fertility crisis against the backdrop of a power struggle within the Council of England, with Theo’s cousin ruling as warden but by the end of the novel, Theo has taken on both the Coronation Ring (making him temporary leader) as well as ownership of the first baby born in a generation, which he baptizes. The film opts for a quieter take, with Owen’s Theo simply trying to find safe passage for pregnant refugee Kee (Claire-Hope Ashity) to the Human Project, a mythical organization trying to find the cure for humanity’s infertility. The movie also expands on Theo’s relationship to the immigrant-rights group the Fishes, which includes his ex-wife Julian (Julianne Moore) and their history of losing their child, instead of them all being relative strangers to one another. By prioritizing the emotional stakes over political intrigue (though there’s still plenty of that in the background), the film resonates and feels much closer to our present while still presenting a dystopia that’s not so far-fetched.

Edge of Tomorrow

While Doug Liman’s time loop alien war movie follows the premise from Hiroshi Sakurazaka and Yoshitoshi Abe’s manga All You Need is Kill, the context necessarily changes when you transform Japanese recruit Keiji Kiirya into an inexperienced American public affairs official named Major William Cage (Tom Cruise). Both are part of the United Defense Force (UDF) that has been created in response to the invasion of alien “Mimics,” but Cruise’s protagonist begins his cinematic journey at a big disadvantage, too cowardly for his posting where he quickly gets killed after getting drenched in Mimic blood.

Except that Cage wakes up again on the morning of his assignment, and realizes that he will be thrust into battle with the Mimics over and over unless he can figure out how to—per the film’s tagline—live, die, repeat. We love a steep learning curve and a transformative journey, especially when Cage’s unique training comes at the hands of war hero Sergeant Rita Vrataski (Emily Blunt), who it turns out earned her own accolades in the same Mimic time loop, only to lose it via a blood transfusion. So while the book’s Keiji and Rita are time looping together, in the movie Cage and Rita trade his knowledge of the ongoing loops with her combat experience.

Furthermore, the book’s time loops come from hundreds of Mimics known as “antennae”; the movie has just one “Omega” that controls the loop from one place and knows how to trick those unlucky loopers with false visions and other traps. Finally, All You Need is Kill pits Keiji and Rita against one another, since either represents an antenna to the other, while Edge of Tomorrow has them falling in love against the specter of death and restarting the loop with one of them not remembering being in the literal and emotional trenches together.

Annihilation

Coming off his mind-bending success with 2015’s Ex Machina, in 2018 writer-director Alex Garland adapted Jeff VanderMeer’s 2014 novel Annihilation into an appropriately trippy film that both called back to the ominous source material… while interpreting it into something radically different onscreen than on the page. The general premise is the same, as an all-female expedition made up of scholars, scientists, and soldiers venture into Area X, a region of what was once Florida that has been transformed by some otherworldly elements. While the group are known only by their functions in the book—biologist, anthropologist, psychologist, surveyor—the movie gives them names to go with the familiar faces portraying each member, plus a linguist making them a quintet: Natalie Portman (the biologist and protagonist), Tessa Thompson, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Gina Rodriguez, and Tuva Novotny.

Both works have major WTF vibes, but the book goes more for psychological horror regarding what the biologist discovers in Area X, while Garland leans all the way into body horror by way of mutated animals and humanoid plants in “the Shimmer”—so named because of the actual change in the air and along its borders. It’s interesting that each story has its own unique visuals, like the oddly-named “Tower” (actually a staircase curving into the earth) that the biologist encounters in the book, which becomes a lighthouse in the film instead; versus Garland’s interpretation on how the Shimmer transforms its interlopers by way of grief and madness.

Even the methods that both stories use for exposition differ with the medium; the biologist learns key details about her husband’s prior unsuccessful expedition into Area X via his journals, while Portman’s Lena discovers video footage of her husband Kane’s (Oscar Isaac) ultimate fate at the hands of a doppelgänger. While the Annihilation novel ends with the biologist venturing further into Area X, as the book is just the beginning of the Southern Reach series, the film employs a familiar device in which Lena returns home to Kane, but it’s unclear if either of them is the same person who went into the Shimmer. Not surprising since when Garland was adapting the film, he had only the first manuscript to go by, so it makes for a more resolved (if still ambiguous) ending than VanderMeer’s series.

Stardust

Neil Gaiman’s darkly comic 1999 fantasy novel (illustrated by Charles Vess) and Matthew Vaughn’s more whimsical adaptation start and end in roughly the same place, but take very different tonal routes to get there. Naïve suitor Tristan Thorn (Charlie Cox) promises to retrieve a fallen star as a token for his supposed beloved, only to discover that the star has taken human form as Yvaine (Claire Danes), who is trying to make it back into the sky. While simultaneously pursued by a trio of bumbling princes fighting over succession to the throne, and Lamia (Michelle Pfeiffer), a witch hungry for immortality by way of literally consuming Yvaine’s heart, the two forge a bond and begin to fall in love.

A key expansion of the novel, and what I most remember from watching the movie in theaters in 2007, was the mid-movie subplot involving a pirate airship helmed by the delightful cross-dressing Captain Shakespeare (Robert De Niro). This charming interlude, in which the pirates teach Tristan how to fight and Yvaine how to dance, really sets the tone for the rest of the film and builds to a confrontation with Lamia that is more action-packed and based on the power of love, yet also more straightforward.

The Prestige

As with Annihilation, here’s another cinematic magic trick in which the writer-director’s take on the source material, while following similar plot beats, becomes its own entity entirely. Christopher Priest’s 1995 novel is billed as science fiction, yet employs a nonlinear narrative including a contemporary framework, where the story almost takes on a ghostly cast: Journals reveal the generations-long rivalry between magicians Rupert Angier and Alfred Borden, the aftereffects of which resonate to their respective grandchildren Kate Angier and Andrew Westley. The facts remain the same, that Angier and Borden compete to create the perfect performance—utilizing doppelgängers and more mystical forms of doubling—in which the magician appears to be magically teleported from one place to another. The key detail in Priest’s novel is that Angier’s trick involves not so much splitting one man into two, but transferring consciousness from an original body (which then becomes a shell) into a new one. When Borden interferes with his trick, Angier gets split into his corporeal form and a more insubstantial one. It is eventually revealed that the same fate befell young Andrew (born Nicholas Borden), and that it is Kate’s fault; the sins of the fathers continue on.

By contrast, Christopher Nolan’s 2006 film is an 1890s period piece, albeit with similar speculative elements, focusing on the magicians’ self-destructive rivalry by creating unique but equally devastating ways in which each man sacrifices for the sake of his act. Nolan kept Alfred Borden’s (Christian Bale) arc from the novel, in which this seeming individual is revealed to be a lifelong performance by twin brothers. But instead of only one appearing in public, they constantly switched roles between Borden and his manservant Bernard Fallon, so that one was always hiding in plain sight. The same went for the women they loved and the children they raised.

Then there’s Robert Angier (Hugh Jackman), who never manages to transfer his consciousness but instead constantly clones himself thanks to Nikola Tesla’s (David Bowie) device—but he never knows if he is the Angier who teleports across the room, or the one who drops into the water tank hidden beneath the stage, and certain death. Told in a mostly linear fashion, but with key doubling-back points to reveal the prestige behind the tricks, Nolan’s version feels like the purest distillation of how rivalry destroys two (well, three) men’s lives.

Howl’s Moving Castle

Many a fan of Hayao Miyazaki’s 2004 animated film would be forgiven for not realizing that the source material was Dianna Wynne Jones’ 1986 fantasy novel (which inspired two sequels, Castle in the Air and House of Many Ways). For one, Miyazaki reshapes Jones’ archetypal fairy tale setting into more of a steampunk world, primarily characterized by a brutal war between kingdoms, which was Miyazaki’s criticism of the United States’ 2003 invasion of Iraq. The constant conflict between nations heightens the book’s central plot, in which a young girl named Sophie gets transformed into an old woman, with her only hope to track down the wizard Howl to reverse the spell.

While the novel is mostly told from Sophie’s perspective, with her growing fond of the initially exasperating and vain Howl, the movie spends more time in Howl’s head and even time travels into the past to show how these two were fated to meet and fall in love. Both works see Sophie pushing back against gendered ageism in her society, but Miyazaki’s vision makes for a more expansive and visually indelible tale.