The Holdovers Ending Isn’t as Sad as It Appears

Alexander Payne's The Holdovers is a bittersweet character study, but there's a reason it is becoming a feel-good Christmas movie in spite of the film's seemingly cold ending.

This article contains spoilers for The Holdovers.

“Waste no more time arguing about what a good man should be. Be one.” – Marcus Aurelius, Meditations

Though a dark horse in this year’s Oscar race for Best Picture, it’s no surprise that Alexander Payne’s latest dramedy, The Holdovers, is primed to clean up—or even upset—key acting and screenplay categories. Less of a candy-colored spectacle than Barbie, and certainly not as gravely bombastic as Oppenheimer, this quiet and philosophical story is all about messy, painfully ordinary mortals finding hope and redemption in everyday gestures.

Smart and well-structured as an original script, the performances of the three central figures are what really brings The Holdovers to relatable life. So much so that while the broad strokes of the movie’s ending seem unfair and cruel, viewers are still left smiling, with many calling The Holdovers a new Christmas movie staple. How did that happen?

A Couple of Lifelong Holdovers

“Always go out on a high note,” as a different luckless philosopher-jerk opined in Seinfeld, circa 1998.

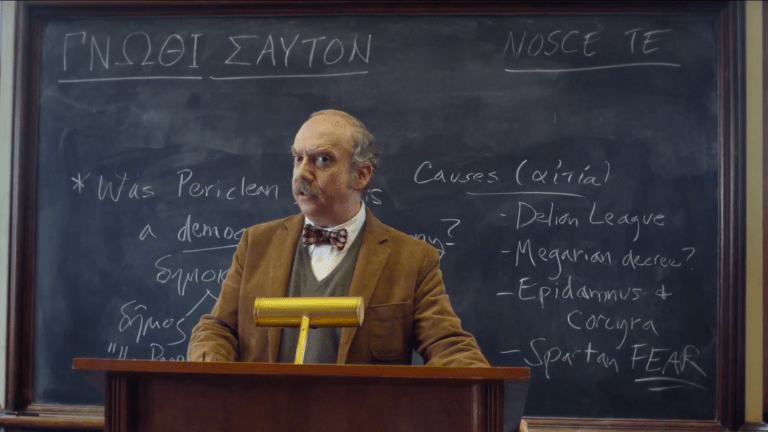

Paul Giatmatti’s Paul Hunham could certainly be a spiritual cousin to George Costanza on that ‘90s sitcom, although Hunham is much more book smart. Played with nuance by Paul Giamatti (Sideways, Cinderella Man), Hunham is an unpopular, misanthropic Ancient Civilizations professor at the fictional Barton Academy where he’s forced to spend the two-week Christmas break chaperoning a few students who can’t visit their families—aka the holdovers. But don’t let the cozy New England boarding school setting, the historical nostalgia, and the recitation of classic literature fool you; The Holdovers is the anti-Dead Poets Society.

Robin Williams’ Mr. Keatings never openly called his students degenerates, nor was he in turn mocked by those students with Hunham’s nickname “Walleye.” Hunham also disdains the ugly politics of his workplace. Indeed, his uncompromising failure to give the entitled son of the school’s biggest donor a passing grade is what got him punished with babysitting the misfit holdovers. The most resentful holdover of the group is Angus Tully (Dominic Sessa in his film debut). Angus and his attitude aren’t well-liked by most other students either. He’s especially surly after getting ditched by his mom, who would rather spend Christmas with her new husband. He’s also prone to getting expelled from school despite being the only student able to pass Hunham’s class. It therefore seems underneath his sneering is a kid genuinely empathetic to other outcasts.

Just not Professor Hunham. Not yet.

Circumstances soon unfold to make Angus the sole student left behind, forcing him and Hunham into closer proximity. Even then, Hunham’s still fixed on rules and established order. He was once a Barton student too and often remains a step ahead of Angus’ plans to leave the premises. Hunham does have a moral code, of sorts, inspired by his favorite Roman and Greek philosophers, which he uses more as a shield than guiding principle.

Hunham talks to Angus a lot about the platonic ideal of a “Barton man.” They never lie or misbehave, they get good grades and go on to the Ivy League, and become, well, literal “kings of New England,” as Michael Caine’s character in The Cider House Rules says to the young men in his charge. Barton men are supposed to be destined for greatness.

But that was untrue during Hunham’s school days and is painfully false in 1970.

Take for example Calvin Lamb. He was a promising, popular graduate of Barton Academy, only he was Black, and unlike the vast majority of his classmates, the son of a single mother who took a job managing Barton’s cafeteria to pay for her son’s tuition. There was no money for college, so when he was drafted into the Vietnam War, he was looking forward to attending college on the G.I. Bill upon his return. Only he was killed in action. His mother Mary, (yeah, a name about as unsubtle as Payne’s own would be in a screenplay) is spending her first Christmas without Calvin alone at Barton too.

Da’vine Joy Randolph (Only Murders in the Building) is by far the favored winner for Best Supporting Actress at the Oscars this year. Randolph turns the problematic trope of a Black female matron figure on its head. Between herself, Hunham, and Angus, Mary is particularly isolated in her fresh grief and has little emotional energy for nurturing anyone. Her pointed distrust of the little rich white students is clear when she won’t eat the dinner she prepared with them. Hunham and Mary bond over bottles of whiskey in her faculty apartment, making gentle fun of the rich jerks around them and their crappy, craven boss, Woodrup. Angus soon edges closer to these older holdovers, seeing them separately from their official Barton roles.

Hunham, it turns out, returned to the safety of Barton only a few years after graduating from the prep school. Other classmates graduated from Ivy League schools and attained that promised success—Woodrup was even a former student of Hunham—but Hunham isn’t at Barton to inspire anyone or to excel at his own career.

He’s society’s unwanted holdover, with a frankly unbelievable amount of unfortunate metaphorical medical conditions including hemorrhoids, a lazy eye, and to really make sure audiences know how off-putting Hunham is, the extremely rare Fish Odor Syndrome. He literally stinks and perhaps that’s why he is resigned to masking his odor with too much bourbon and cigarettes.

Although, in fairness, it is 1970 and if the smoking indoors didn’t give it away, the fact that there’s actual snow on the ground every day of December sure does.

A Boy with a Chance to Get Out

While Hunham wrestles with his lost opportunities and Mary with her pain, Angus is also struggling with a secret personal loss that makes him lash out—which is the dramatic peril of the story, for if he gets expelled from Barton Academy, he’ll be shipped off to military school and from there, most likely, Vietnam. Nonetheless, Angus still has his reasons for desperately wanting to sneak away to Boston for the winter break and after much, much convincing, Hunham, Mary, and Angus take an unauthorized overnight visit that ends with revelations all around.

This test run at life beyond Barton gets Hunham out of his comfort zone, which he discovers was never really all that comfortable. He may espouse the social theories of Marcus Aurelius, that “we are all equal in the end,” but that isn’t enough, dammit. People like Hunham are limited by circumstances beyond their control, whether by birth or a disposition that becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Mary is even more of a have-not in this country, and Angus will likely face her dead son’s fate if he can’t find a way to work in a system that Hunham failed to successfully navigate.

Success for these characters means facing their past losses, letting their walls down, and finding togetherness in other people. The Holdovers is all about the divide between past and present, and Payne’s nostalgia for ‘70s era filmmaking infuses his movie with heavy nods to road trip classics like Paper Moon and Harold and Maude, complete with Cat Stevens on the soundtrack. What keeps it from getting too sugary-sweet is just how flawed its main characters are—they drink too much, they push people away, they lie and disobey.

They are not hypocritical, entitled “Barton men,” but they are, by and large, good people. They want desperately to feel safe and loved and welcome. It’s the little connections and common grounds that can keep the Have-nots going.

A Happy Ending Full of Loss, Uncertainty, and Joblessness

Unfortunately, when Angus’ mother finally learns how her son spent winter break, she complains to the school that Hunham took Angus to Boston to visit his father in a psychiatric hospital without her permission, and against Mr. Tully’s apparent medical recommendations. Woodrup assumes that Angus outsmarted or bullied Hunham into the unauthorized field trip. But recognizing that Angus will get expelled and sent to military school, Hunham takes the blame and gets fired from the only job he’s ever had.

While he gets a satisfying moment to tell Woodrup what an asshole he is, Hunham is most comfortable with the unknown future ahead of him. Will he at last go to Greece? Will he write his book? Will he maybe find love in romantic forms? He doesn’t know. But he’s given Angus another chance to change his ways, live with honesty, and live up to the bright future he has time to make for himself. Mary, too, is inspired by Hunham’s surprise stand and channels her hope and love toward the impending birth of her sister’s child.

These holdovers aren’t healed entirely, but they’re on the right path. Despite being jobless and homeless, knowing that so much time and regret is behind him, Hunham is finally living up to the true ideals he’s romanticized since boyhood. By taking the fall for Angus, he at last demonstrates the meaning behind the Cicero quote he so pointedly threw in Woodrup’s face at the beginning of the movie.

“Not for ourselves alone are we born.” And isn’t that a message we can celebrate all year round?

The Holdovers is streaming now on Peacock.